Compared to many of my fellow novelists, the research could hardly be described as arduous: making choux pastry and deliberately allowing the mixture to catch. I was trying to describe a baking disaster and had convinced myself the only way to do so was to act it out. The smell of burnt sugar filled my kitchen as the pan’s sides burned, and lumps of egg and cornflour congealed into sweetened scrambled eggs.

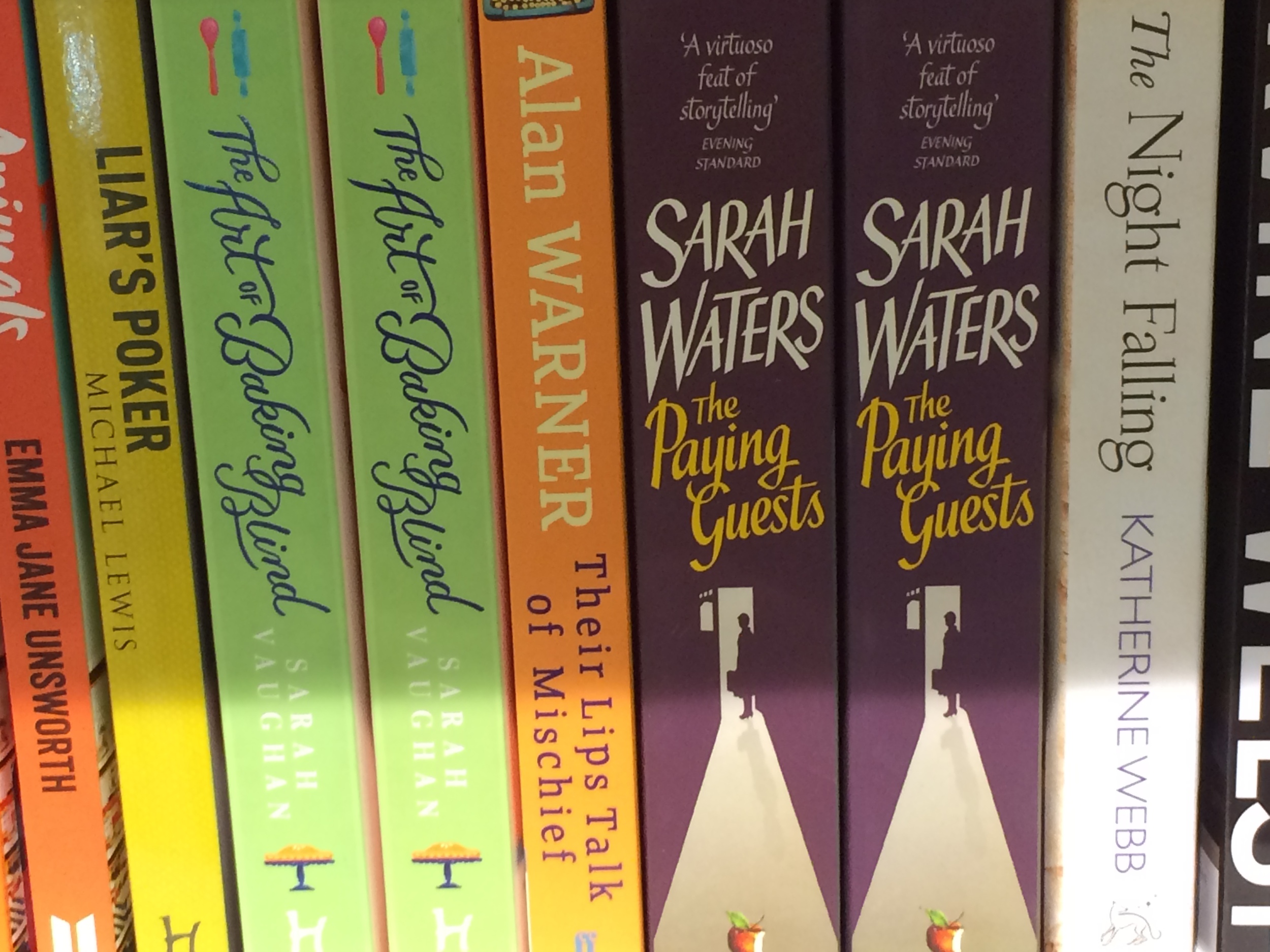

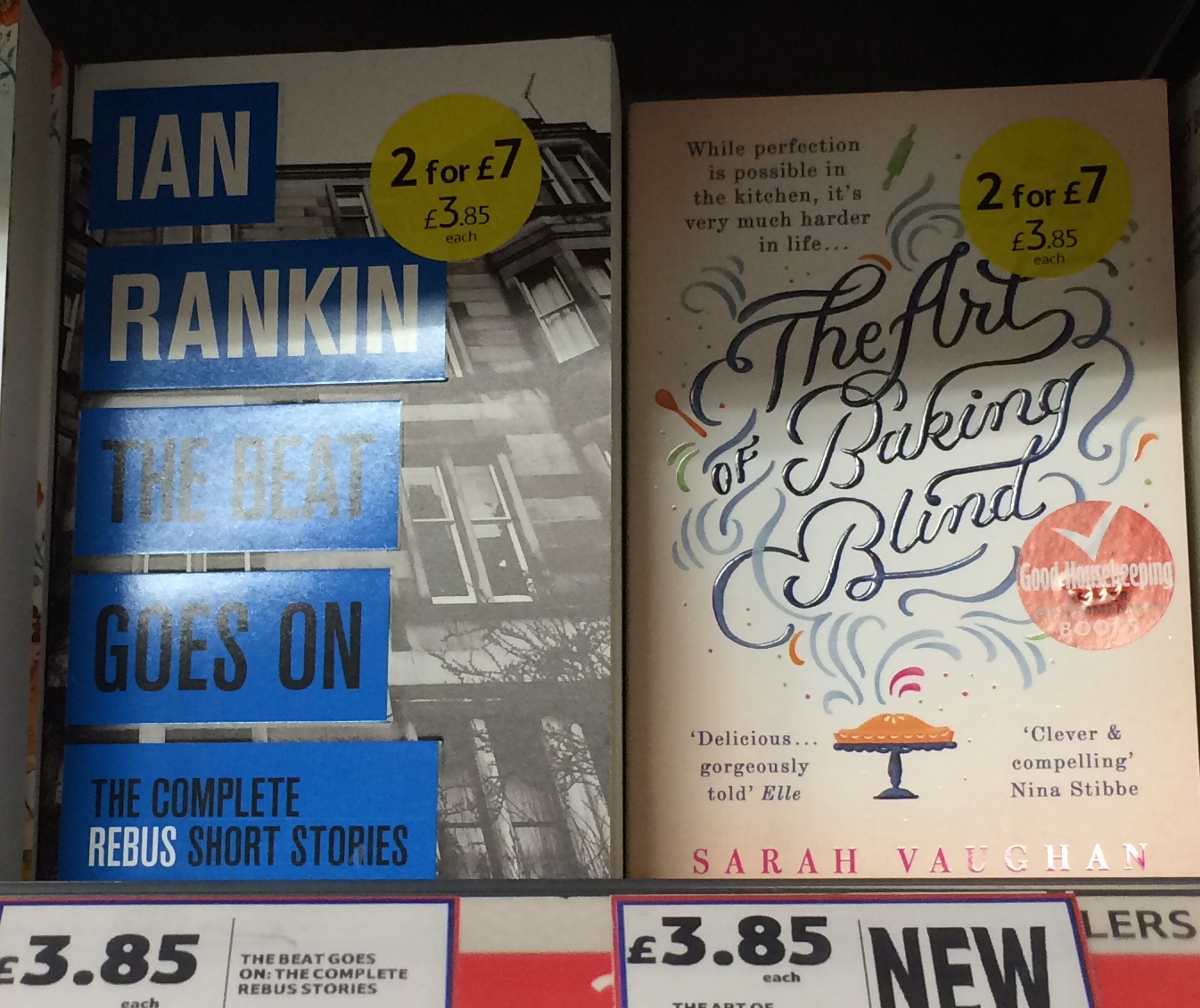

As The Great British Bake Off enters its patisserie week, I was reminded of this moment, which came as I finished my novel about why we bake. Despite my mother excelling at that 1970s dinner party staple, profiteroles, and my making a mean crème pat, I had never attempted choux. But writing The Art of Baking Blind, a novel partly inspired by the GBBO, taught me to push my culinary boundaries. Forget method acting, this was method writing: immersing myself in a world of melted butter and sugar; of egg whites whisked into stiff peaks, and rising dough. Cocooning myself in the scent of warmed cinnamon and nutmeg; learning how to make a patisserie at the heart of my novel - the tarte au citron.

Mango coulis, citron crème pat, ganache, choux, a galette base: patisserie for the launch of the French edition of The Art of Baking Blind, La Meillure d'Entre Nous.

I first came up with writing a novel about why we bake as I made sponges and gingerbread men with my small children. For me, baking was the perfect way of doing something creative while proving that I was a good mum. If that sounds extreme, I’d given up a job as a senior reporter and former political correspondent on the Guardian to freelance and be a stay-at-home mother. Used to writing every day, I wanted to mix and churn, to beat and whisk, and crucially to come up with something delicious at the end of it. Because that way I was not only achieving something but I was showing my children – with my roast chickens and homemade stocks, soups and risottos as well as my cakes and biscuits – just how much I loved them.

I realised I was over-investing my baking with emotion when I took a tin of homemade chocolate chip cookies, made with my four-year-old, to some new friends on a play date. “Talk about showing us up!” laughed another mother, her tone distinctly brittle. “Can’t you just bring a packet of jammy dodgers like everyone else?”

I began to think about why I bake and what motivated other bakers I knew: the mums decorating exquisite cupcakes for the school fair; the stick-thin mother who had heaped my plate with birthday cake as a child; the contestants who put themselves through competitions like GBBO, who were willing to spend hours spinning sugar or constructing gingerbread houses they knew would immediately be demolished. Because I was sure that our obsession with baking wasn’t just about nostalgia in a time of recession – though that may be part of it - but about the fact that we can we can work through all sorts of emotions while we create with eggs, fat, sugar and flour.

Profiteroles sold in Le Marais, Paris; filled with rose water or chocolate crème pat and sometimes gilded with gold leaf.

With this in mind, I used the characters in my novel to illustrate different reasons we bake. For Jenny, a housewife and mother whose daughters have flown the nest, it remains a way to prove she loves her family, even if they no longer need her. But it’s also a habit, a means of working through her emotions, and a way of connecting with a happier past.

For Vicki, who remembers her childhood kitchen as “a cold room…in which she ate supermarket quiche and watery iceberg,” baking with her son is a means of providing him with the loving childhood she lacked. Constrained by motherhood, the baking competition also allows her to do something creative and to carve out some time for herself.

For Mike, a widowed father, baking not only provides some validation but is therapeutic, while for Kathleen Eaden, the cookery writer whose 1966 cookbook, The Art of Baking, inspires the baking competition and informs the novel, baking is such an extension of her personality that what and when she bakes mirrors her mood and reflects the plot.

And then there is Karen. For if most of the novel’s associations with baking are positive, for her there are more sinister connotations. She doesn’t bake because she is frustrated or needy, like Vicki, but because she is a perfectionist for whom baking is the ultimate means of control.

Launching the French version of The Art of Baking Blind, La Meillure d'Entre Nous, in Paris earlier this year, I kept being reminded of this, my most troubled, character. For patisserie is the form of baking which, more than any other, demands self restraint and an obsessive attention to detail.

I could see this in the patisserie created for the Livre de Poche launch: delicacies involving passion fruit gel on mousse au citron with sesame tuile and black sesame crème pat, or citron crème pat and black sesame shortcrust, topped with a tiny, sesame-dusted meringue. It was evident in the shops specialising in exquisite profiteroles or sables biscuits; confections sandwiched with mango, vanilla, chocolate or citron crème pat, and laid out beneath glass cabinets as if they were expensive jewellery; and even in the blowsy displays of more traditional patissiers: the glossy tarte aux fraises; the rich curls of dark chocolate; the plump religieuses; the dinky macarons and expertly-constructed millefeuille.

I spied these sentiments, too, in the readers who discussed why the bakes in my novel were not as creative - or as accomplished - as those in their patisseries; or who gently pressed me to taste their creations.

One reader had spent the day making 100 macarons in seven different flavours - including blackberry, citron, pistachio, chocolate and raspberry - for a friend's macaron pyramid birthday cake; a feat she pulled off while racing through 100 pages of my book. "You're a good friend," I commented as I bit into her tiny, light-as-air pistachio creation and listened to the coos of other women doing the same; and she shrugged, in self-deprecation. "It was nothing." She had pulled off the ultimate trick: patisserie that was perfect but that claimed to be effortless.

Her answer, though, also conveyed the motive that I think is at the heart of most baking. For while we may bake out of neediness, because we're frustrated, competitive or suffer from what French Elle describes as "the tyranny of slimness", most of us bake "in the spirit of generosity" as the BBC's Martha Kearney, herself the winner of the Comic Relief Bake Off, has said.

Or as Kathleen Eaden declares in my novel: "There are many reasons to bake: to feed, to create, to impress; to nourish; to define ourselves; and sometimes, it has to be said, to perfect. But often we bake to fill a hunger that would be better filled by a simple gesture from a dear one. We bake to love and be loved."