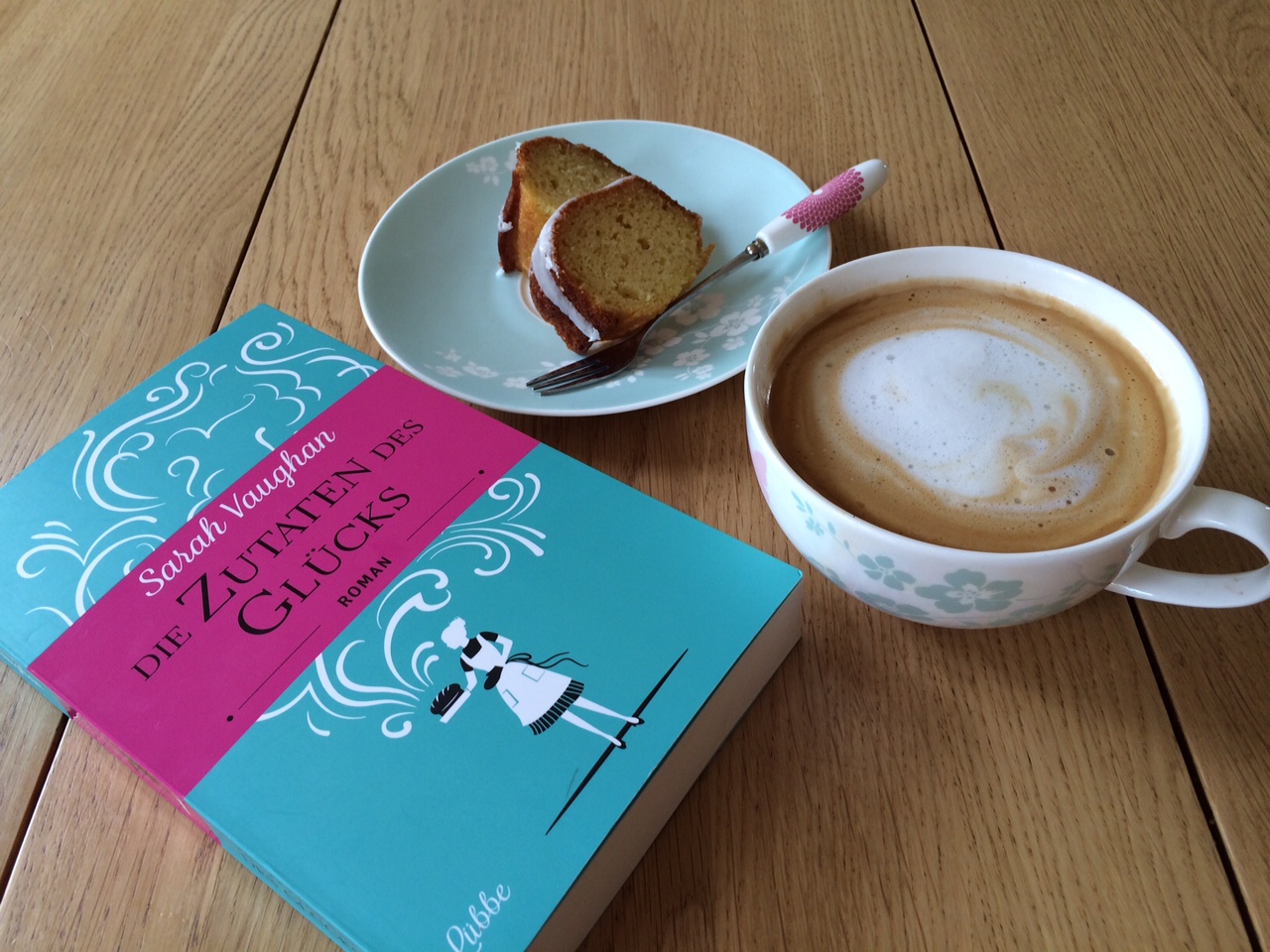

I found these vintage baking accessories in a Parisien salon du the, and while I would usually be lured by the patisserie, these were the items that drew me in.

My first novel, The Art of Baking Blind, features a fictitious 1966 recipe book, and I could see its author carefully weighing ingredients decanted from such jars before concocting her millefeuille. Kathleen Eaden attended the Le Cordon Bleu before my novel began - and, as I feasted on these covetable kitchen accessories, I imagined her life outside my pages: a late teenage rebellion; an affair with a pastry chef; late nights and early mornings fuelled by coffee stored in tins like these:

Perhaps it's no surprise that, as a writer, I covet vintage things. Despite knowing that most "preloved" finds are tat, I'm drawn to old china, books, furniture: anything with the potential to trigger a story.

I live in an eighteenth-century cottage that we renovated. And as we opened up chimneys and pulled at floorboards, it kept revealing secrets; glimpses of others' lives. Who hid that toy soldier up the chimney? Or buried the 1930s advert for slimming aids? Or the glass bottle labelled arsenic in the garden? Who owned these pieces from the past that kept whispering their tales?

Then there are the vintage finds I’ve picked up at jumble sales or local auctions: a delicate coffee cup and saucer, etched in gold leaf; mismatched crockery; a 1950s pitcher with “Jug” somewhat unnecessarily stamped on it. A child’s eighteenth-century rocking chair, bought for £70, whittled in oak by a father, and revealing a name graffitied by a small girl: Ivy. A French-polished writing box, belonging to a grandfather who took poetry books to war and lost them when captured on Kos; my grandmother’s locket, which I can never open without catching the scent of her.

I never thought I would write historical fiction but it now seems inevitable that the past would worm its way in. "The past kept pricking at me," explains LP Hartley's narrator, in The Go-Between, and it's a quotation that could preface many of the novels that fascinate me.

We are the sum of our past, as well as our present and future, which surely explains the burgeoning interest in genealogy and the existence of programmes such as the BBC's You Do You Think You Are? as well as our nostalgic hankering for vintage things. "The past is not a package one can lay away," as Emily Dickinson said. And we see that throughout our culture - from watching Downton to being fascinated by World War II to visiting National Trust houses. And yes, to purchasing accessories inspired by the 1950s or 60s: those Tala measuring jugs; or Keep Calm and Carry On cards, which work precisely because we know they are a play on Kitchener's iconic poster. Because we share that history.

When writing about a farm in north Cornwall, run by the same family for six generations, it seemed obvious, then, that I would draw on my own family's past and in particular the stories my mother told me of spending her childhood summers on a Cornish farm.

But though her recollections fed into it, I needed a prop: some tangible evidence that would sit on my desk and inspire me as I pushed through the third draft, and the fourth, fifth and sixth. Something that would whisper its past to me, when I was feeling sluggish; that along with my photographs of the area, would prompt me to think: "what if?" and, "and then what?"

This sepia photograph does just that:

It shows my great grandfather, Matthew Henry Jelbert, hoeing mangolds on Trewiddle, his farm, just outside St Austell. He looks slightly shy yet rather proud as he leads his shire horse and the plough. Dressed for the camera, he sports a tie, white shirt and collar, gold fob watch and luxuriant moustache. His farmhand waits discreetly, for this is Matthew’s moment, even though the horse, the most expensive animal on the farm, dominates the picture.

Matthew Jelbert was born in 1880 in Newlyn East, towards the tip of Cornwall, seven miles from Truro and Newquay. He died in 1970, two years before I was born, yet both he and his farm - or rather the tales of them - played a vivid part in my childhood.

The summers spent there in the Fifties were the happiest of my mother's early years. Her father, Maurice, was a Methodist minister. But when he helped with the harvest he was just a farmer’s boy and she was freed of the constraints imposed on a minister’s daughter.

She would run wild with her cousin Graham, eighteen months younger than her but, growing up on a farm, more worldly-wise. They would climb trees; blow birds’ nests; hide in the stooks of corn; play doctors and nurses under the rhododendron bushes. A chalky stream ran at the bottom of the field, from the china clay pits, and she believed that it was milk, and Trewiddle, heaven. For a child expected to go to church three times on a Sunday, it was quite literally the land of milk and honey.

Trewiddle held such a strong sway over me as a child that I named my doll’s house and its connected farm after it. And when I came to write my novel, about a granite farmhouse on a remote stretch of the north Cornish coast, my mother and her cousin’s memories, and the photos of the farm, weaved their way in.

Great grandpa Matthew watches me, now, as I type.

My past is pricking at me. I am taking liberties with it. But I hope I do it justice.